A brief introduction to our secular perspective

The purpose of this first post is not to give an in-depth look at market history or to discuss at length what the long-term macro picture is likely to be, but rather to provide a sound analysis of the current market situation. However, in order to better contextualize said analysis, we feel it’s important to make our readers aware of what our secular perspective is.

We are of the opinion that a secular bear market in equities started in March 2000 (this opinion is probably shared by anybody who has not lived under a rock during the course of the last decade). Secular bear markets tend to last on average approximately 17 years and at their secular bottoms they tend to reach certain specific and depressed valuation levels which in turn give rise to new secular bull markets. As we shall endeavour to demonstrate during the course of this post, such depressed valuations levels have not only not yet been reached, but not even approximated. This, the fact that according to historical records we still have some 5 years or so to go and certain macroeconomic considerations (a succinct summary of which you’ll find in the next paragraph) lead us to believe that we still remain mired in a secular bear market.

Secular bear markets all display certain characteristics, one of which is the alternation of cyclical bear markets with cyclical bull markets. During the current secular bear, we’ve witnessed two cyclical bears, followed by two cyclical bulls, the last of which is the current one. Historical precedent tells us that we should expect at the very least another cyclical bear market, more likely two.

With that in mind, let’s see why we think we may be on the verge of one of those nasty cyclical bears, but not before having covered some basic economic theory.

The money printing fallacy

“But the Fed will not allow the stock market to plunge”, “With all this money printing stock prices are bound to increase”, “QE(insert number) is stimulating the economy and putting it back on track”, we can almost hear the sceptics say. So let’s quickly deconstruct these arguments and show why money printing (these days euphemistically called Quantitative Easing in Newspeak) is not helpful to the economy at all and, as an obvious consequence, ultimately hurts stock prices as well (even in extreme situations, when money printing goes berserk à la Zimbabwe, stocks fail to make any real advances, i.e. they fall when measured against gold). To all the readers brave enough to venture on their own in the realm of macroeconomic theory we suggest to read the important classics of the Austrian School of Economics, like “The Theory of Money and Credit” and the intimidating “Human Action” by Ludwig Von Mises and “Man, Economy and State with Power and Market” by our beloved Murray Rothbard. We strongly encourage all the other readers, who do not have this somewhat masochistic vocation or simply lack the time to engage in such in-depth readings, to visit Pater Tenebrarum’s blog

Acting Man: there he provides a very useful and always excellent commentary on the economy and markets and in our opinion does a great job at simplifying and summarizing rather complex concepts in a clear and concise way.

What is money? Money is the general medium of exchange, the thing that all other goods and services are traded for, the final payment for such goods and services on the market (Rothbard, Austrian Definitions of the Supply of Money). Is money synonym with capital? No, capital represents the so-called “pool of real funding”, it is saved consumption (i.e. lower order goods) which can be used to fund investments in higher order goods (e.g. new plants, machinery etc.) with the goal of increasing productivity and achieving economic progress (i.e. doing more with less). All investments have to be funded with capital (that is: real resources that were saved before and that are now taken out from the economy’s pool of real funding to sustain the investments). Money alone does not suffice. However the fact that capital is often expressed in terms of money constitutes the basis for a pernicious misidentification.

What do money printing or the expansion of fractionally reserved bank credit do to the economy? Because of the public’s conflation of money with capital, they fool economic actors into believing that there is more capital available than it’s actually the case. They encourage investments in higher order goods that appear sustainable when they really aren’t (because the economy has the money/credit, but doesn’t have the actual real resources to fund such investments that this money/credit purportedly represents). The longer this shell game continues, the more capital is wasted in the process, further reducing the pool of real funding and thus undermining the economy as well as its future prospects. Sooner or later reality sets in and all the endeavours that appeared to be profitable because of this fictitious abundance of capital are revealed for what they truly are: malinvestments that need to be liquidated. This happened many times before (inter alia 1929, 1965, 2000, 2007) and is happening again now:

The ratio of Industrial Production of Business Equipment to Industrial Production of Nondurable Consumer Goods and the S&P500 index (right scale, logarithmic). The graphical demonstration of our point: all unsustainable fiat money-driven spikes in the ratio of higher order to lower order goods need to be painfully corrected. Notice the strong correlation of such corrections with bear markets. It is important to note that Corporate CAPEX has been extremely high as well as of recent: not really a bullish sign.

As such, money printing cannot achieve what it should supposedly achieve, namely to bring about economic prosperity. What it can achieve is to delay the inevitable and, in so doing, make it worse.

With these objections now out of the way, let’s get down to business.

Fundamental Conditions

In this section we intend to show you why in our opinion a new cyclical bear market is likely just around the corner. We will cover two main points: the current stage of the business cycle and the current level of stock valuations as well as the rationale behind them.

A) Where we are in the Business Cycle

A premise: there are plenty of indicators out there which track (or supposedly track) economic trends and we are well aware that not all of them confirm what we are about to show below. However if a recession were obvious no profit opportunity would currently exist. Moreover some of those indicators aren’t in our opinion reliable, as they’re either lagging rather than leading or they’re based on shaky theoretical foundations. Generally speaking we tend to favour indicators which track the performance of the manufacturing sector, as it represents the core of economic activity. We also tend to dislike indicators based on GDP or GDP growth, as we’re not at all fans of this specific aggregate (and of economic aggregates in general), although now and then we do employ it to calculate ratios (and will do so below). We may some day write a more theoretical post on the many weaknesses of GDP and other popular indicators, but for now this will suffice. Of course we encourage our readers to do their own research on the topic. Finally, although we’ll only show US data below, we’d like to briefly mention that the December Markit manufacturing PMIs came in as follows: JPM Global 50.2 (up from 49.6 in November: back in slightly positive territory after a few months of contraction); Eurozone 46.1 (down from 46.2 in November: still no end in sight for the 18-month-and-running contraction); Germany 46 (down from 46.8 in November: in contraction mode since March 2012 with 18 months of falling orders…anybody wants some DAX futures?); Japan 45 (down from 46.5 in November and currently sitting at a 44-month low, with investment goods demand contracting the most).

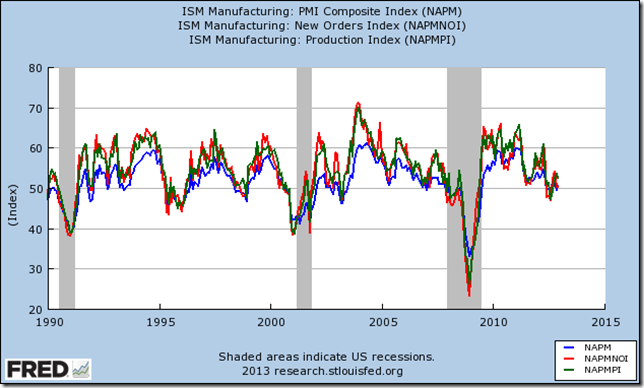

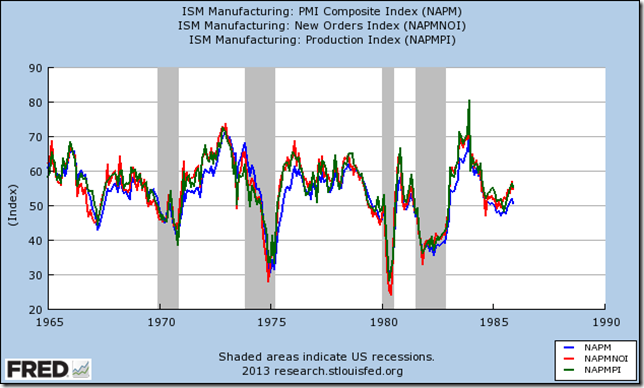

The first chart we show in this section tracks the performance of three popular indicators published by the Institute for Supply Management: the New Orders Index, the PMI Composite and the Production Index. They generally tend to be leading indicators, although to varying degrees, with the New Orders Index being our favourite one.

PMI Composite, New Orders and Production Index: their ability to anticipate recessions can be clearly gauged from this graph.

As can be seen above, all these three indicators have been flirting with contraction territory for quite some time (remember that a reading above 50 signals expansion, whilst one below indicates contraction; the same applies to the Markit PMIs further above). Sceptics may point out the undeniable fact that these aren’t infallible measures, as they often give false signals, as in the period from 1990 to 2000. However one always has to contextualize information: back then we were in the second decade of a very powerful secular bull market, whilst right now we find ourselves in the second decade of an equally powerful secular bear market. To further prove this point, let’s see how this indicator fared during the last secular bear market (1965-1982 or 1967-1982 depending on interpretations):

Same indicators as above, from 1965 to 1985.

It becomes clear that false signals become way less frequent, particularly as the economy enters the tail end of the secular bear cycle. Our contention is that we are today in a very similar situation: we are approaching the final and always more painful years of a secular contraction which, as we must never forget, was born out of an egregious bubble of unmatched magnitude.

The second chart tracks the evolution of an indicator known as Smoothed US Recession Probabilities, which was created by economists Marcelle Chauvet and Jeremy Piger. Readers interested in exploring how this indicator is constructed and its workings can do so

here. It is important to note that the indicator undoubtedly confirms a recession after it has long happened: if one wants to profit from its use one has to act in a sort of “twilight zone” of uncertainty (as is always the case in financial markets as well as in life in general). It is also worth mentioning that, given the way in which it is calculated, it is published with a delay of roughly two months (i.e. the last reading currently available refers to the month of October): this adds an element of uncertainty as well (one has to act early or risk “missing the train” as two mere months can induce a lot of change in the markets). With that in mind, let’s see what it tells us:

Smoothed US Recession Probabilities: the last reading refers to the month of October and came in at 7.34%.

We can notice a quite unpleasant spike in recession probabilities as of late. The last readings were as follows: July 0.6%; August 4.5%; September 4.8%; October 7.3%. Clearly, the trend so far is up and the rate of change tends to be quite dramatic, i.e. we are unlikely to see a quiet and progressive increase: this stems from the fact that recessions tend to happen quite abruptly. False signals are rare: the only one worth mentioning happened during late 2005. The two spikes recorded in the late ‘70s were soon followed by the 1980 recession. So the question becomes: is this recent increase likely to be a false signal? You decide! But we’d tend to think it’s not.

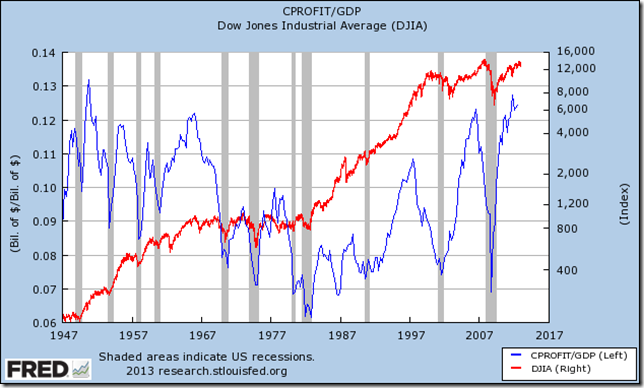

Finally we’d like to include a chart which shows Corporate Profits with Inventory Valuation Adjustment and Capital Consumption Adjustment as a percentage of GDP, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average superimposed (right scale, logarithmic) :

Corporate profits as a percentage of GDP: currently at nosebleed levels and they got there with an astonishing vertical rise to boot! Notice how during bear markets peaks in the ratio tend to anticipate important tops in the stock market.

We can make two important observations with regard to the graph above. Firstly, Corporate Profits currently are at very high levels relative to GDP, when viewed in an historical context. This makes us think that further economic expansion seems improbable at this stage, since this is exactly what we've already got for the last four years and corporations have benefited handsomely: does this look sustainable? Secondly, the correlation between this ratio and stock prices tends to be rather weak during secular bull markets and strengthens during secular bear markets: this might be explained with the fact that during secular declines profit margins as a whole tend to be more dependent on the economic cycle, as it frequently and dramatically swings from expansion to contraction, whilst during secular advances they are influenced by a wider array of factors and recessions tend to be less frequent, milder and only temporary. Not surprisingly, the ratio usually peaks before the stock market does and as of now it has apparently topped already: are we going to see this relationship continue? Keep in mind that since the start of the current cyclical bull market in 2009 Corporate Profits growth has been impressive and is unlikely to continue on this path: mean reversion appears to be a more probable outcome, hence further upside in the ratio above should be capped.

These considerations, as well as many other and maybe more conventional ones which we won’t cover here, have us thinking that a major turn for the worse in the business cycle is likely to happen fairly soon. Chances are, it may have happened already and its effects are going to become evident during the course of Q1 and Q2 2013.

B) Equities are Overvalued

Although deteriorating economic conditions are a necessary factor in provoking a bear market, they are by no means sufficient: we also need to have generous and overly optimistic stock valuations. Something we’re apparently getting as well! Before proceeding with the analysis, we’d like to acknowledge the excellent work done on this topic by

HussmanFunds in their

Weekly Market Comments. We were recently involved in a discussion on equity markets at

one of our favourite blogs: a reader argued, somewhat bizarrely, that HussmandFunds’ lacklustre performance somehow disproves the validity of their research. As any real trader or investor knows, doing great analysis and employing it profitably are two very different things (by coincidence,

their latest missive thoroughly and convincingly addresses this criticism and explains their long-term strategy as well as its basis). We are of the opinion that their work is not only interesting, but more importantly rooted in actual facts and sound arithmetic calculations. We also recommend our readers to have a look at the valuation research of

Doug Short as well as at his other work: we do not always share his views, but he always makes for an interesting and thought-provoking read. We will present below a selection of charts from these two sources.

The first graph plots a number of valuation metrics against their arithmetic mean (for the record, Doug Short also shows the same metrics compared to their geometric mean) and the distance between the CPI-adjusted S&P Composite and its exponential regression line:

Crestmont P/E, Cyclically Adjusted P/E (CAPE 10) and Q Ratio compared to their arithmetic mean and the distance between the CPI-adjusted S&P Composite and its exponential regression line. For the sake of brevity, we’ll leave it to the interested reader to investigate the details of these valuation measures and their validity or lack thereof. More information can be found here, here, here and…here!

It appears evident that a) the overvaluation levels reached in 2000 were egregious, whilst those reached both in 2007 and presently look quite scary as well(in fact the ‘60s bull market peaked at or below those levels); b) neither in 2002 nor in 2009 did we reach the levels of undervaluation usually associated with secular bear market bottoms (actually we didn’t even come close to those levels) and considering the overshooting to the upside of Y2K we wouldn’t be surprised to see an equivalent one to the downside. An important caveat is that of course such undervaluation levels do not necessarily have to be achieved by means of a collapse in nominal stock prices (1970s bear market docet).

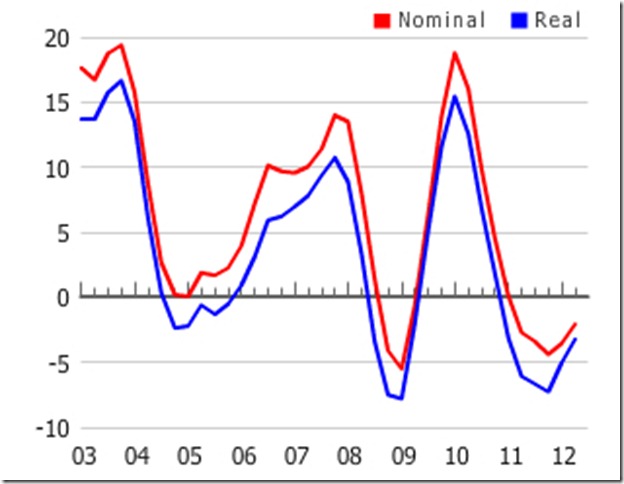

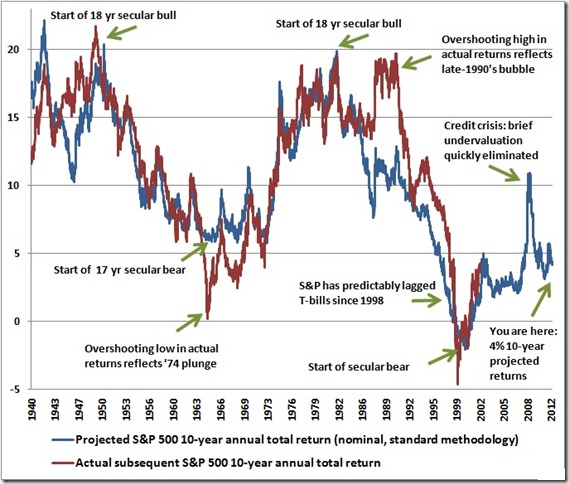

So let’s now see what kind of nominal returns can an investor reasonably expect in the current valuation environment:

S&P500 Projected 10-year total annual return in nominal terms(details on the calculation method here) and the subsequent 10-year total annual return in nominal terms actually achieved by the index.

The same projections made using different valuations methods and the actual subsequent return. Extracted from this article.

As can be gauged from the charts above, the 10-year total nominal return a prudent investor (one who does not recklessly gamble in hope of finding the proverbial greater fool) should be expecting based on current valuations lies somewhere around 5% per annum. Historically, this is where bull markets tended to peak, rather than bear markets bottom: the latter occurred when prospective total annual nominal returns where around 20%. Buyers beware!

It should be remembered that these generous valuations arrive at a time when earnings/corporate profit margins have likely peaked (earnings growth has already been decelerating for quite a while and has recently turned negative during Q3 2012, as reported by

Factset).

Technicals, Sentiment and Positioning

The final section of this post will cover a variety of timing tools which we find useful in helping us assess the likelihood that a major market turning point is approaching. Again, this is not meant to be a comprehensive list: we just want to show some of the more interesting and maybe some of the lesser known technical and timing indicators we use.

We’ll start by including a somewhat arcane technical indicator, developed by

McClellan Financial Publications: the previous year’s Eurodollar Commitments of Trader Report can be used to ascertain the likely direction of the S&P500 index. For some background on why this may be the case, please read

here. We’ll present the most recent chart published by McClellan and then we’ll show you the graphical representation of the 2011 and 2012 Eurodollar Commitments of Traders Report.

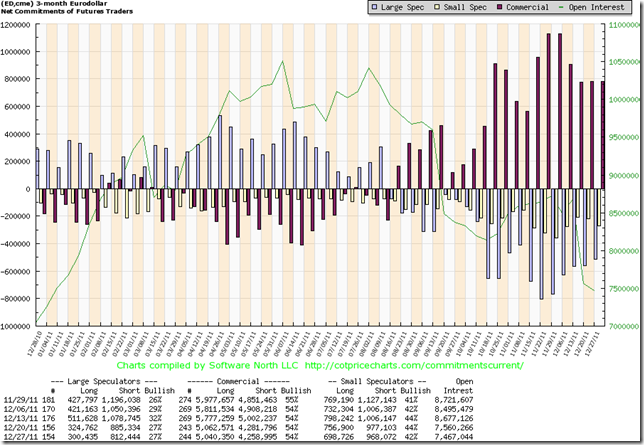

Commercials’ positioning in the Eurodollar market: major tops in the S&P500 tend to occur about one year after major peaks in commercials’ net long exposure.

Traders’ positioning in the Eurodollar market during the course of 2011 according to data from the CFTC CoT reports: commercials’ net long positioning peaked around the end of November. Chart via http://www.cotpricecharts.com/

We want to warn readers that this is by no means a perfect indicator: it can and does give false signals and even correct signals may be of the mark by a few months. However we’ve found it to be useful, particularly when one focuses only on extreme readings (like the opposite ones registered during November 2011 and September 2012). According to this tool, the stock market may have already peaked and is unlikely to find a major bottom before this autumn.

We will now show a very simple yet informative breadth measure: the percentage of S&P500 stocks above their 200-day simple moving average, with the S&P500 index superimposed:

The S&P500 index and the percentage of its components above their 200-day SMAs: the latter has been declining since at least the spring of 2011. Chart constructed using http://www.indexindicators.com/.

The chart above shows that the participation rate in the last major advances has been constantly declining: notwithstanding new cyclical bull market highs, today 80% of stocks are in a long-term uptrend, as opposed to more than 90% at previous major market tops. Rising prices in the face of declining participation tend to signal weakness. We are aware of the fact that other breadth measures do not support this conclusion, but we think this simple indicator does a better job at measuring the health of the market than many more complex others.

It should be noted that other important bearish divergences exist: most notably long term RSI and MACD divergences and declining volumes of trading. This all combines into a picture of deteriorating technical conditions that signals a faltering advance likely to top soon.

The Volatility Index confirms the assumption that we’re more likely near the end of a rally rather than at its beginning:

The S&P500 Index against the VIX: volatility is currently very low and during the recent correction it has failed to show the usual behaviour generally associated with major bottoms. Chart via http://www.indexindicators.com/.

A careful look at the graph above reveals that major bottoms are usually accompanied by a meaningful spike in the VIX (at least above 30 and more likely towards 40/45). Moreover after said spikes volatility tends to remain at elevated levels for quite some time, as fear and disbelief accompany the nascent rally and every correction is mistaken for a further continuation of the downtrend. None of these circumstances where present at the recent bottom: the VIX briefly surged above 20 and immediately collapsed and currently sits at 13.8 as of Friday’s close: is this the marking of a major bottom?

Sentiment and positioning tend to confirm our bearish outlook. We won’t include any charts, as many of them are copyrighted, but we’ll instead go through a quick overview.

Sentiment: NAIIM Manager Survey, Market Vane bullish percentage and Hulbert Stocks and Nasdaq readings all stand at rather elevated levels and have been there for a while (a sign of complacency); sentiment on the Japanese yen (a classic risk-off play) currently lies at multi-year lows.

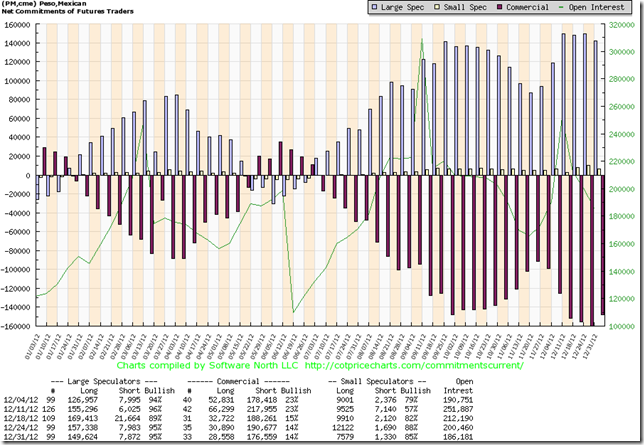

Positioning: NYSE Margin Debt is at very high levels, signalling excessive speculation; Mutual Funds Cash as a percentage of total assets and Retail Money Market Funds as a percentage of market capitalization both lie at extremely low levels, signalling complacency and an active participation in the current rally on the part of dumb money; the spread between US Treasuries and risky bonds (High Yield and Emerging Market Bonds) currently sits at very low levels, rarely seen outside of the mid 2000s bubble years; traders’ positioning in the Japanese Yen and in the Mexican Peso both stand at opposite extremes (speculators are heavily short the former and equally heavily long the latter: this is an incredibly ominous sign that never fails to materialize at important market tops). [Ed. Note: one of our next posts is likely going to cover currency markets in general and the Japanese Yen in particular, as we believe it might prove to be a wonderfully performing long in the months to come.]

We show below the graphs of traders’ positioning in the Yen and Peso, to wet the appetite of the contrarians amongst our readers (a note on CoT charts: the persistence over time of very large speculative commitments, in either direction, is always more worrying than episodic spikes):

Traders’ positioning in the Yen: the last time we saw a higher commercials’ net long position was at the end of June 2007. Chart via http://www.cotpricecharts.com/.

Traders’ positioning in the Mexican Peso: as far as we know commercials never held such a large net short position, at least not after 2004. Other notable extremes regularly occurred in concomitance with major stock market tops. Chart via http://www.cotpricecharts.com/.

Conclusion

We remark once again that all of the above is simply an overview (although an extensive one we believe) of the current situation and does not constitute a complete market analysis. We have however performed such an analysis and we can confidently state that it confirms the view expressed above, namely that from both a fundamental and a technical perspective we’re fast approaching an important market top that will likely signal the beginning of a new cyclical bear market of unknown magnitude (we note however that at least a test of the important support zone around 1000/1100 on the S&P500 appears likely). We can not yet ascertain whether this top has already been reached: we shall endeavour to provide a real-time update if and when we become convinced that said top is in. We do note here that this mostly concerns active short term traders: we are long-term investors and we like to establish our positions at approximate turning points, when we become convinced that a major shift in trend either has occurred or is about to occur and that consequently the potential reward of the trade dwarfs the potential risk. In this specific case, we think that it’s highly unlikely that the S&P500 will close 2013 having gained more than 10% (this is our worst case scenario), whilst the possibility of a 30% or more peak-to-trough decline appears very real. Given the above, we have started to purchase put options on major stock indices, including the S&P500 and the Dax30. We have also opened some company-specific shorts

[Ed. Note: we won’t generally comment or provide coverage on single companies. To readers interested in this field, we suggest checking out the work of Reggie Middleton of BoomBustBlog fame: we subscribe to his services and are deeply satisfied with the quality of his research.]. As always, we encourage all our readers to perform their own analysis.