The objective of this post is to clearly delineate the reasons behind our recent Yen bullishness and to explain why we think buying it against the Australian and New Zealand dollars is likely to prove a very profitable and relatively safe speculation. We need however to immediately point out that everything we are going to write below is conditional upon the Bank of Japan continuing to do what it has always done (and what we think is likely to continue to do), namely to say one thing and then do another (or slowly do just a little of that one thing). In case the demented Abe is capable of fully enforcing his delirious inflationary views on the BoJ, then dear readers brace yourselves and prepare for the Misesian “disastrous bull market”… This is the main reason why we advocate implementing the trade with a judicious use of call options on the Yen (or put options on the Aussie and Kiwi), as they both buy us time and protect us from unwanted catastrophic scenarios that, although unlikely, could nonetheless materialize. With the above in mind, let’s begin our analysis.

The Fundamental Backdrop

A) Japan’s Money Supply growth is both modest and lower than that of other major currency blocks

Leaving aside temporary phenomena which might impact it, the long-term value of a currency is mainly determined by its supply and demand dynamics: in the end it will tend towards the level where demand and supply converge. So the main question an investor has to ask himself is: what is the current supply/demand status quo and how it is likely to be impacted by future developments?

We won’t cover here all the factors influencing the demand side, apart from briefly mentioning that during periods of economic turmoil society’s reservation demand for money (see Rothbard, “Man, Economy and State with Power and Markets” - Chap. 11) tends to sharply increase (as a reflection of the increased uncertainty market participants face). Of course such demand will tend to focus on those forms of money which, correctly or not, market participants perceive to be of highest quality. This is the formal explanation behind the safe haven trade and the reason why during the last crisis the Yen and the Dollar benefited handsomely at the expense of other, less trusted, currencies like the Euro. We will instead focus on the supply side.

As can be seen in the chart above, sourced from the highly recommended blog of Michael Pollaro, Japan’s True Austrian Money Supply growth has been muted in recent years (readers interested in learning what this money supply measure contains and why, as well as in which respect it differs from commonly used metrics like M1 and M2, can do so here and here). Even more importantly, given that currencies do not trade in a vacuum but rather against each other, it has been consistently lower than those of other important currency blocks like the U.S., the Euro area and the U.K (not shown in the chart above and yet important to mention is the fact that BoJ’s credit has only recently reached its old 2005 peak, whilst other central banks have tripled, quadrupled or even quintupled their credit since the beginning of the financial crisis).

There are two main reasons as to why this has been (and may well continue to be) the case: on the one hand, the BoJ has been reluctant in injecting large doses of newly created money into the economy, notwithstanding all their posturing; on the other hand Japanese banks have been more than happy to grab the chance to engage in massive deleveraging (a.k.a. credit contraction), thus counterbalancing to a large extent the effect of money printing (it should be noted here that inflation is correctly defined as an increase in the supply of money and money substitutes). Going forward, the second factor is likely to remain unaltered, given that the sorry state of the Japanese economy and the increasing likelihood of a globalized slowdown mean that banks are probably going to be unwilling to extend new credit (please see chart below). So the question becomes whether the BoJ will truly print enough to overcome the deflationary effect of credit contraction and to outdo its competitors in the mindless race to devalue (on this last point please see our paragraph below). We are inclined to think that much of what we’ve heard so far is little more than political manoeuvring and that in the end they won’t seriously alter the status quo lest they may finally wreck the ship, given that Japan’s precarious position does not allow much if any room for “funny money” experiments. The BoJ’s meeting this week will give us some clues as to the likely direction they’ll take, although the actual implementation of their programs is what matters most.

A chart showing first the decline and then the almost non-existent growth of credit in Japan, via http://www.tradingeconomics.com/.

We recommend our readers to have a look at all of Michael Pollaro’s charts on Japan’s True Austrian Money Supply as well as his work on other currency blocks. We also suggest reading this WSJ article, in which the author points out that Abe’s inflationist policies might upset some powerful sectors of the business establishment (not to mention many other innocent people as well as the poor chaps at the bottom of the economic ladder, who always suffer the most from such insanity). Incidentally, this has so far been the only mainstream article we have been able to find which didn’t contain gloomy predictions about the Yen’s imminent demise and which didn’t simply regurgitate some expert’s opinion about why shorting the Yen is going to be the greatest thing since sliced bread…

B) Other Countries are unlikely to let themselves be outprinted by the BoJ

We have already mentioned the fact that so far the BoJ has shown remarkable temperance in its money printing (and that other central banks have not), but should they decidedly change course, what are other countries going to do? Are they going to let themselves be “outprinted” by these latecomers in the inflation game? On this topic we can do no better than pointing our readers to this excellent article written by the always excellent Pater Tenebrarum, which closely mirrors our own views and even includes a nice haiku for the discerning reader. It appears clear to us that the fallacious and highly damaging mercantilist approach is going to be embraced (or has already been embraced) by most nations, thus making any devaluation attempt on the part of the BoJ unlikely to succeed (particularly if half-hearted).

C) The influence of Capital Repatriation (i.e. carry trade and Japanese overseas investments)

This point analyses in more detail one of those temporary phenomena which might impact the value of a currency: the sudden shift of large amounts of capital from one currency block to another. As we have already witnessed during 2008, when a serious, unexpected crisis strikes, massive quantities of money, which previously headed, during the course of many months or even years, in a certain way, are quickly moved back in the opposite direction, thus causing extremely powerful trends in the currency cross involved. This can be likened to the effect that suddenly opening the floodgates of a large dam has on the underlying brook.

In the case of the Japanese Yen, we think there are at least two factors which might contribute to this phenomenon materializing: the infamous carry trade and the repatriation of foreign holdings on the part of Japanese investors.

The former is certainly no longer as large as it once used to be, both because many speculators got badly burned during its 2008 dramatic unwind and because the spread amongst yields has been steadily diminishing. However, the fact that the hunt for yield has become even more desperate and the stable if mild uptrend which many risk currencies (like the AUD or the NZD) enjoyed against the Yen since the post-crisis rebound of 2009 might have induced at least a modest resurgence of this phenomenon. A generally low level of forex volatility that reached its apex during last summer probably also played an encouraging role. It’s important to note that this is only speculation on our part, as we do not have any concrete evidence to back our claims.

The latter factor, on the other hand, has in our opinion the potential to generate the kind of outsized forex move we’re looking forward to. Japanese investors hold a staggering $3.3 trillion of foreign assets, which amounts to roughly 55% of their annual GDP. The Ministry of Finance holds approximately $1.27 trillion in exchange reserves, whilst the remaining $2 trillion are held by the private sector. During a crisis, either out of fear or out of necessity, some of these holdings are liquidated and the proceeds repatriated: this has an obvious boosting effect on the Yen. This is exactly what happened during the spring/summer of 2011: both the massive earthquake that shattered Japan in March and the mini bear market that shook global markets during the summer induced capital flight and thus generated a quite powerful rally in the Yen, which took place notwithstanding a globalized manipulative effort to the contrary on the part of the G-7 (which was capable only of producing a temporary spike in late March of 2011). We expect this to happen again, only on a much larger scale, during the coming bear market.

As to why we chose Australia and New Zealand as the main counterparties to our long Yen campaign (apart from the specific reasons outlined in the paragraph below), please consider the following: roughly 80% of Australian government bonds and 70% of Australian corporate bonds are owned by foreign investors (sources here and here); the situation in New Zealand in not much different, with 62% of government securities now held by foreigners. We suspect this is going to have a huge negative impact on their currencies in case of a global crisis. The icing on the cake is that Japan’s investments in Australia total more than $123 billion and account for 6% of all foreign investments in the country (placing Japan firmly in the third place, behind the U.S. and the U.K.). Almost half of this sum is invested in Aussie bonds, in a desperate hunt for yield. There are signs that this phenomenon is accompanied by dangerously high levels of complacency and euphoria ("If you think there's been a lot of investment from Japan in Australia so far, just you wait and see," Mr Beazley said. "The Australian economy looks and feels extremely secure."). Finally, the traditionally risk-averse Japanese individual investors have recently started to become excited about the U.S. and other foreign equity markets, exactly at a time when caution would be advised.

D) A Brief Introduction to the Australian Bubble

We will now briefly cover the main reasons which stand behind our calling Australia a bubble.1. Brisk monetary growth, both in absolute terms and when compared to other countries:

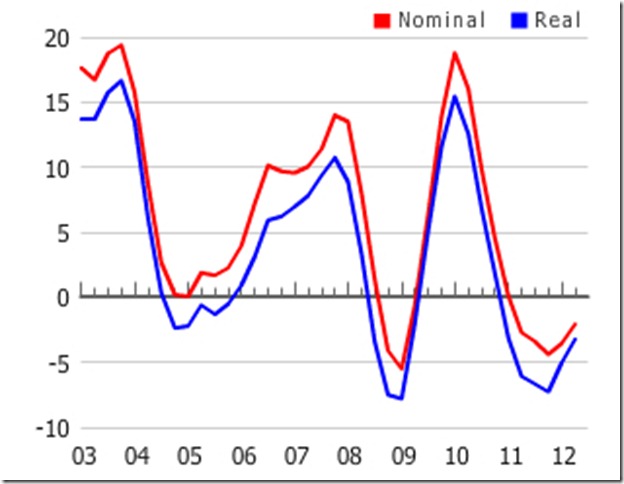

The hallmark of all bubbles: monetary growth. M1 in Australia, the U.S. and Japan, indexed at 100 in January 2005.

A long-term chart showing the annual percentage changes in M1 for the same three countries. Australia has often led the way.

It appears clear from the charts above that there has been remarkable inflation going on in Australia for at least two full decades and we know that with inflation malinvestments and capital consumption inevitably occur. Japan on the other hand has certainly been the least bad of the group, something which we already remarked above [Ed. Note: since we do not have True Money Supply statistics for Australia, we are using M1, which acts as a decent proxy.].

2. Large amounts of debt, mainly concentrated in the household sector:

Household debt as a percentage of GDP: higher than in the U.S.

Australian households are buried in debt: if the economy barely sneezes, they’ll get pneumonia. In this context, it’s worth nothing that the latest PMI reading (December 2012) came in at 44.3, marking the 10th consecutive month of contraction, and that the overall picture painted by the report is rather bleak: interested readers can find more info here.

3. The always-present real estate bubble:

Year over Year % change in real estate prices in Australia, via Global Property Guide.

It’s quite obvious that there’s a massive property bubble in Australia. Other indicators looking at affordability (namely price to income and price to rent ratios) also signal massive overvaluation. Mortgages account for a large part of the astronomically high household debt [Ed. Note: readers can find some interesting info here. We also think that the whole blog is worth keeping an eye on.]. When will this bubble pop, as they all inevitably do? We wouldn’t rule out it’s already in the process of deflating, given that we’ve had two years in a row of declining prices (recall how in the U.S. prices topped in 2005, roughly two to three years prior to the actual bust) accompanied by declining sales in both the residential [Ed. Note: forget the mindless babbling of the article’s author and instead just focus on the chart at the top of the page.] and commercial sectors. Moreover, point 4 below might prove to be the prick that this floating balloon needs so badly.

4. Australia’s fate is highly dependent on China:

Exports to China constitute roughly 29% of all Australian exports, with Iron Ore accounting for more than half of the total, with Coal, Gold and Oil distant followers (all data sourced here). It’s not difficult to envision what would happened in case the much-talked-about Chinese hard landing materialized. As a side note, we’re highly sceptical of the Chinese boom as well, given that it’s built on the shaky foundations of money and credit inflation, coupled with massive state intervention in the economy (which all result in malinvestments and capital consumption). Curious readers could embark on their own research on the topic: we’ll just mention that ghost cities are amongst our favourite manifestations of the massive misallocations and imbalances currently plaguing China, mercantilist extraordinaire.

Technicals, Sentiment and Positioning

From a technical perspective, the Yen is severely oversold and incredibly stretched below its long-term moving averages (like e.g. the 200-day simple moving average):

A chart showing the Japanese Yen Index, via http://stockcharts.com/.

It’s important to note that the index above tracks the movements of the Yen against a basket of currencies and that the levels reached against certain currencies (like e.g. the Euro, the AUD, the MXN and the NZD) are even more extreme.

Yapanese Yen Futures Positioning, via http://www.cotpricecharts.com/.

Positioning in the futures market is also remarkably elevated, with small speculators holding a record amount of shorts and large speculators’ shorts at a multi-year high (significantly higher levels were recorded during the summer of 2007, right at the peak of an egregious bubble and at a time when the carry trade was still buoyant). It’s worth mentioning that this is accompanied by opposite extremes in AUD and MXN positioning, thus showing a propensity toward risk-taking and generalized complacency. We briefly mention here that record CoT readings in risk-on and risk-off currencies usually provide very reliable contrary signals on the stock market as well.

Finally, sentiment on the Yen lies at multi-year (possibly all-time) lows, with Sentimentrader’s Public Opinion Survey showing only 16.5% of bulls, after having spent quite some time in the below-neutrality zone. Moreover, the Yen is universally hated: we have yet to see somebody who is not bearish on it. Pundits and talking-heads as well as many self-appointed experts have all been quick to point out how the currency is doomed, how shorting it is going to be the best trade of 2013 (when in fact it most likely was one of the best trades of 2012...), how the BoJ will inflate ad infinitum etc. As the heading of one of our favourite blogs reads: "When it's obvious to the public, it's obviously wrong."

The conclusion is clear: rarely have we seen such extremes and they have never proved to be the hallmark of a sustainable trend.

Moreover, an investor has always to ask himself: what is the market already discounting? It appears to us that in this specific case the market has already priced in many negative developments, some real some most likely not, leaving ample space for positive surprises.

Moreover, an investor has always to ask himself: what is the market already discounting? It appears to us that in this specific case the market has already priced in many negative developments, some real some most likely not, leaving ample space for positive surprises.

Conclusion

We are very bullish on the Yen and we are convinced that the best way to position ourselves is to buy it against fundamentally weak currencies like the Aussie Dollar. The important caveat is that the mental Abe could really wreak havoc on the country and consequently on its currency, given that Japan truly is just a little inflation away from total disaster. We always prompt our readers to engage in their own research. In our next post, we’ll discuss how secular bull markets generally end and which common traits they tend to share at such a juncture: as you’ll see, the Yen currently displays none of them.

Addendum

The BoJ set a 2% inflation target and embraced open-ended asset purchases: we have to confess that we are rather pleased to see this outcome, given that on the one hand it deprives the hallucinated Abe of the possibility to attack the Bank and on the other it gives the Bank itself the flexibility to decide how much and when to print (whereas a fixed monetary goal would have forced them to act and would have always elicited calls to "do more"). Moreover, there wouldn't be any additional money printing until 2014. We'll now have to watch like hawks how this new program is implemented (and whether the appointment of the new BoJ governor in April will change the landscape significantly), as this is what really matters: should the BoJ really print ad infinitum, then it would be game over; should they decide to continue to deliver only a modicum of money printing now and then, as they've always done, then the secular Yen bull market should resume its advance. So far the market's reaction gives us cause for optimism: at least a short to medium term rebound is likely in the cards, as too many jumped too quickly on the short yen boat.

Addendum

The BoJ set a 2% inflation target and embraced open-ended asset purchases: we have to confess that we are rather pleased to see this outcome, given that on the one hand it deprives the hallucinated Abe of the possibility to attack the Bank and on the other it gives the Bank itself the flexibility to decide how much and when to print (whereas a fixed monetary goal would have forced them to act and would have always elicited calls to "do more"). Moreover, there wouldn't be any additional money printing until 2014. We'll now have to watch like hawks how this new program is implemented (and whether the appointment of the new BoJ governor in April will change the landscape significantly), as this is what really matters: should the BoJ really print ad infinitum, then it would be game over; should they decide to continue to deliver only a modicum of money printing now and then, as they've always done, then the secular Yen bull market should resume its advance. So far the market's reaction gives us cause for optimism: at least a short to medium term rebound is likely in the cards, as too many jumped too quickly on the short yen boat.

No comments:

Post a Comment