The goal of this post (whose title is again going to titillate music aficionados) is to give our readers a quick overview of the state of roughly 20 real estate markets around the world. We’ll purposefully omit countries where the bubble has already clearly burst (like Spain, Ireland or Cyprus), although in many of them the downside may still be severe. A notable exception is the U.S., where the savvy policies of the bearded monetary shaman have helped bring the housing bubble back from the dead.

Germany's housing market so far hasn't managed to enter bubble territory, although the recent influx of scared money, coupled with the ultra-loose policies of the ECB are beginning to work their voodoo.

We intend to start with a brief Austrian explanation of the origin of bubbles and how come they often manifest in the RE sector and we’ll then move on to the actual description of the various RE markets, for which we’ll use a combination of statistical data, third party research, anecdotal evidence and direct experience (we’ve been to many of the countries mentioned and we’ve also had a stint in the construction business a few years ago). It’s worth noting that we’re currently short via long-dated put options (although a paper we recently read and on which we may comment in a subsequent post has had us reconsidering the wisdom of buying long dated options, rather than continuously roll-over short-dated ones) a few banks such as CBA in Australia, BNP in France, RY, BNS and CM in Canada: they’ve been binging on RE during recent years and we suspect they won’t be cheering once it becomes obvious that the party is over.

As an aside, we still have to understand why exactly perpetually rising real estate prices (in the face of massive oversupply to boot) are held to be such a boon for an economy, as they only bring about more debt and/or a decrease in disposable incomes as they keep on tying up more and more resources.

On the Origin of Bubbles

Unless one believes that bubbles are a “gift” of God or the inevitable result of the evil capitalists’ activities, the first thing one has to ask himself is “How come there are bubbles?” and the second one is “How come they always (or at least very often) seem to appear in certain specific sectors of the economy (like e.g. real estate)?”. The answers to these very important questions lie in the thorough study of the theories formulated and expounded by the Austrian School of Economics and in particular by its two heavyweights Mises and Rothbard. If one does not wish to read roughly 2.500 dense pages of actually very sound and interesting economic thinking, then we can suggest him to at least have a look at this great article on the production structure assembled by the always excellent Pater Tenebrarum, whose blog we highly recommend and on whose work we’ll rely rather extensively during the course of this post. Here, we’ll just give a short, to-the-point answer to the questions above, simplifying and summarizing more complex concepts that inevitably need other venues to be treated exhaustively.

First of all, we need to recognize the fact that the production structure (i.e. the productive chain that starting from raw resources and labour delivers a final consumer product) is made up of different stages: higher order (like e.g. real estate, the capital equipment industry etc.) and lower order ones (like e.g. your grocer around the corner). These stages are defined according to their distance from the final consumer goods the production of which is always the ultimate goal of the economy: all factors of production, whether original (land/natural resources and labour) or produced (capital goods) are always employed to produce a final consumer good somewhere down the road (i.e. a trashing machine being built today with the use of raw resources and manual or mechanical labour will one day harvest grains that will then be consumed as food). It is important to note that there exists a lag between the beginning of the production process at the highest order and the actual production of the final consumer good (i.e. you can’t produce an iPhone if you haven’t designed it or built the necessary tools and machinery needed to assemble it). The longer the production structure, the longer the lag. It obviously follows from this fact that all investments in the production structure need to be funded by real resources that have already been both produced and saved (since the additional consumer products that will be produced as a result of these investments won’t be available before a certain lag); also, the financing of higher order stages of production requires significantly more resources than the financing of lower order ones, due to the fact that it takes longer for them to yield a final consumer good with which to repay the investment. In the trashing machine example above, we already need to have the grains with which to feed the labourers employed in its construction: we can’t make them work without subsistence whilst waiting for the machine to be completed and the next harvest to begin, no matter how loudly Paul Krugman argues for such an idiotic approach (by the way, we’d love to see him starve whilst trying to prove that you can indeed put the cart before the horse). Money simply facilitates this process: instead of paying our workers with grains, we give them money and they’re free to spend it according to their needs and wants. But the fact remains that we can only fund production with real resources and the appearance of fiat money (via printing and credit expansion) does not magically make appear real resources as well.

That said, how do we go about deciding the allocation of resources between the different stages of production (i.e. how do we decide whether to invest more in harvesting machines or whether to keep harvesting by hand or even whether to further lengthen the structure by investing in the designing of a plant that will produce new and more efficient tools to facilitate our harvesting)? It all depends on our time preference rate, that is it depends on our willingness to sacrifice present consumption (that we need to save to finance investments) in favour of higher, but future consumption. Each one of us of course has his own personal preferences and in a complex market economy where many economic actors interact all these different preferences combine into forming the originary rate of interest (which is nothing but the society-wide time preference rate), in the same way in which buyers and sellers combine in forming the market price for a good. This originary rate of interest is not set in stone, but rather changes as conditions (like e.g. the size of the pool of real funding) and preferences change, again in the same way as prices do. [For the sake of simplicity we omit to mention here the fact that each and every good has its own specific rate of interest and that there exists a never-fulfilled tendency towards the harmonization of all these different rates.] Originary interest combines with a risk premium (dependent on the creditworthiness of the borrower), a price premium (dependent on the expected changes in the purchasing power of money) and an entrepreneurial profit to form the interest rate.

With the above in mind, we can now begin to see how bubbles come into existence and the sectors in which they are likely to occur. The investor who needs to allocate capital (i.e. real, saved resources) relies on the interest rate to facilitate his calculations of which allocations are profitable (by discounting in the present the future value expected to be generated by the various investments). He also uses money as a unit of account and its availability as a proxy for the availability of the real resources this money is supposed to represent. We can now realize that if the money (or credit) is not backed by real resources, if its value is subject to a constant, subtle erosion and if the rate of interest does not truly reflect the real society-wide time preference rate then the investor can very hardly avoid making a mistake in his calculations.

It also becomes clear that the higher stages of production will be affected more by such interferences than the lower stages as the lag between an investment in such stages and the actual production of the final consumer goods is greater and this makes its profitability significantly more dependent from changes in the rate of interest (since the period to be discounted using that rate is longer).

Recalling the fact that investing in higher stages is more resource-consuming, we can see how these false signals that encourage investments in these higher stages in the absence of the required amount of saved-up resources are especially pernicious, as they deprive the economy of significant amounts of real capital that may have been used to satisfy far more pressing needs (as an example think of all the stuff that gets used up and all the people that are employed when building one of the famous “stimulative” bridges to nowhere). Moreover, when it is discovered that the required resources the existence of which was feigned do not actually exist, the re-adjustment process becomes inevitable (i.e. the bubble bursts).

Proof of our assertions can be found in the fact that, as far as we know, we have not once seen or heard of a bubble in greengroceries, with people rushing to open up stores to sell apples and bananas to frenzied consumers (as the grocer buys the groceries wholesale at dawn and sells them throughout the day and does not need any particular capital equipment to carry out his job, he is basically immune from manipulations of the rate of interest, although as readers can see in the article linked in the next paragraph overconsumption takes place during a boom as well and is then inevitably followed by “forced savings” and this inevitably affects the latter stages). On the other hand, we’ve been to many cities with office and residential towers popping up like fungi and where we could see a real estate agency on every corner (or even more often) and meet deluded people who were happy to share their dreams of boundless wealth (of course, they only needed RE prices to go just a little bit higher).

We want to make an additional and apodictic consideration (although we do provide a link here for those who want to further examine the argument): the stage of the production structure most neglected during the boom phase is the middle one.

And with this we end our brief introduction, again stressing the need for way more thorough investigation of the matter on the part of interested readers.

Old Europe

Let’s begin with where we live, the wonderful continent of Europe. Readers interested in knowing more about it, in a heavily stereotyped (and hence fun) way, can watch “Jeremy Clarkson meets the neighbours”: here is the link to episode one!

Netherlands

Here we start with a massive one! It seems to us that the Dutch are suffering from Tulipomania-related nostalgia and as such have been busy blowing a new bubble, and one for the ages!

Household debt to GDP as well as household debt to disposable income ratios of 250% and skyrocketing home prices: an explosive combination! The end result is one of the most overvalued RE markets in the world, that lately clearly appears to be faltering. With 650 billion € of RE loans outstanding, stockholders, bondholders and depositors at Dutch banks beware: you may get Cyprus’d before you know it, as our beloved Reggie often reminds to the Irish!

Two Charts depicting the performance of the Dutch housing market in recent years, via Global Property Guide.

A wee bit of debt currently on the balance sheet of Dutch households, from the previously linked Acting-Man post.

France

Ze French would obviously not tolerate to be left behind by anybody (ah, la grandeur!) and so here we have them, with their RE market right on top of the list of the most overvalued in the world. Depending on the valuation measure used (whether disposable incomes or rents), prices are roughly 35-50% above their long-term average ratios, which means that, according to the law of the pendulum, they are likely to go quite a bit below said average ratios once the bubble pops. We wouldn’t be surprised to see prices at least halve over the course of the coming years, particularly if Monsieur Hollande keeps acting like a lunatic (let’s be honest: he looks like one, doesn’t he?! Have a look here!). It’s interesting to note that in Paris and in the surrounding region overvaluation is even more extreme, likely due in part to the economic and political importance of the area and in part to the huge influx of foreign money (this resembles the situation of London in the U.K., see below). No Pétrus for recent buyers, that’s for sure! A marked slowdown in building activity and a recent decline in sales (which turned into a 44% plunge in the number of transactions in Paris), accompanied by a modest reduction in prices may signal that the party is rapidly ending (readers need to remember here that prices are the last component to deteriorate, with construction activity and more importantly sales acting as early-warning signals). Interested readers can learn more here, here, here, here and here.

French home prices relative to disposable income, divided per region, chart courtesy of CGEDD.

Belgium

Even the tiny country of Belgium has managed to blow a rather sizable RE bubble, with remarkable levels of overvaluation. Interestingly, the market seems to be giving only feeble signals that the unwinding process may be about to begin: prices continue to creep higher (albeit not in Brussels), with the only warnings being a slowdown in construction activity and a decrease in mortgage issuance. We do however doubt that the Belgian bubble could be able to withstand a popping of neighbouring bubbles (France and Netherlands) and/or a new iteration of the global financial crisis (which, as readers of this blog know, we consider to be baked in the cake). Interested readers please have a look here and here.

Belgian house prices: still no sign of collapsing. Chart via Global Property Guide.

Belgian house prices: still no sign of collapsing. Chart via Global Property Guide.

U.K.

The U.K. also sports a severely overvalued RE market, with London being one of the most expensive cities in the world when it comes to buying a house. Prices are at least 30% above their historic valuation ratios. Of course, British blokes are up to their eyeballs in debt (in the Greater London area mortgage servicing takes up on average a whopping 35% of income). And quite naturally the government feels compelled to encourage even more reckless borrowing (we want to reassure the author of the linked article, as there’s no risk of creating a new RE bubble: there already is one that is alive an well!). So far no major warning shots have yet been fired by the market (although there has certainly been a slowdown), however we encourage current RE owners not to feel too safe, as the foundations of the bubble are clearly shaky ones and a new recession or a financial shock may very well prove to be the proverbial nail in the coffin. Other, more detailed information can be found here and here.

The dizzying chart of U.K. real estate prices, via Global Property Guide.

Switzerland

Even the famously dull Swiss have not resisted the temptation of engaging in a massive real estate binge, thanks in part to the mental policies of the SNB (zero rates and a money printing bonanza designed to stop the “harmful” rise of the Franc) and the large inflows of scared foreign money in search of a safe haven (and which may have ended up finding a grave). The result is a horrendously overvalued market where interest-only mortgages are common practice (otherwise many chaps could not even begin to think about buying a home) and where many cities and popular resort towns now sport some of the highest prices per square meter of the whole orbis terrarum. And so the secluded alpine country, famous producer of excellent chocolate and cuckoo clocks of dubious taste, is now drowning in debt, to the tune of 175% of disposable income. Again, there are no clear signs that the end may be approaching. In fact, it seems like the bubble is currently accelerating into its final blow-off stage. Readers are invited to read more here, here, here and here.

A chart of RE prices in Switzerland, which conceals the astonishing increases witnessed by some of the major cities.

Sweden

Even the supposedly safe Northern European countries have taken part in the global RE bubble and they’ve done so with much gusto, as we shall see here. Starting with Sweden, we want to mention that prices have now begun to decline moderately, after having experienced an incredible run-up (more than doubling in the last decade). However RE is still severely unaffordable and at the very least 20% above its long-term average valuations. A household debt-to-income ratio of roughly 175% completes the picture. Signs of a slowdown are now present, but not yet obvious. For more on the topic please click here, here, here, here and here.

Housing prices in Sweden: now beginning to decline after coming close to a triple in less than two decades.

Norway

Norway is not in much better shape than Sweden. Arguably, the situation there may even be worse, due to the fact that its bubble has grown significantly larger than Sweden’s. Proof can be found in the fact that households now sport a debt-to-income ratio grater than 200%, not to mention that RE prices may be as much as 70% above their long-term averages, depending on the valuation metric used. Socialist paradise anyone?! Particularly worrying is that fact that so far there have been few if any signs of More facts can be dug up here, here, here, here and here.

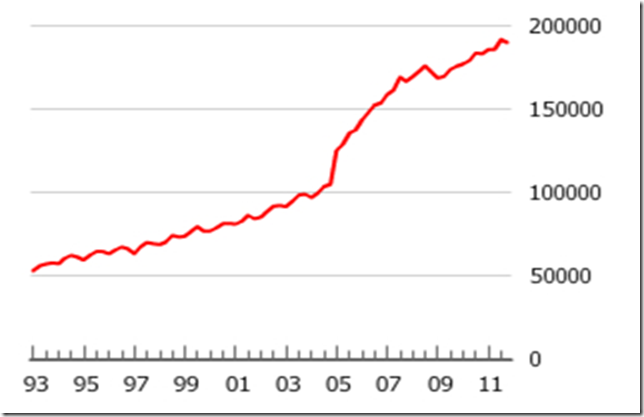

Honestly, we can’t see a bubble here, can you?! A mere tripling in 15 years can’t count as one! Via Global Property Guide.

Denmark

Apparently even the almost inconsequential country of Denmark has managed to blow its own RE bubble and to make sure it was noticed abroad it made it egregious. Maybe exponentially-rising home prices have helped the Danes cheer up a bit, but don’t hold your breath for it. In any case, the solution to the supply-demand imbalance appears simple to us: just build a few Lego houses! Household debt is more than 300% (yes, that’s not a typo) of disposable income and house prices have almost tripled in the last 15 years. Also of note is the sheer size of the nation’s mortgage market: 600 billion € ready to blow up in the face of not very smart holders. The bubble here has clearly burst and the real fun is just beginning, as both the government and the banks scramble to find a way to keep the ponzi scheme going. More info here, here, here, here and here.

The party has clearly ended in Denmark: now it’s a question of who’s going to eat the losses. Chart via Global Property Guide.

Finland

We terminate our overview of European RE markets with Finland, which also has its home-made bubble, although maybe less egregious than those of its neighbouring countries. Debt-to-income is “only” a bit above 100%, but home prices have almost tripled in the last 15 years. As of late the bubble seems to be wobbling, with price appreciation having slowed down markedly. Readers can continue their research here, here and here.

House prices in Finland, via Global Property Guide.

Down Under

We now move to the Southern Hemisphere.

Oz

Australia is where one of the most egregious RE bubble in the world has popped up, thanks in part to the commodities boom and to an enormous credit expansion. Houses are now at the very least 30% overvalued (with 40% to 50% being a more credible estimate), with cities such a Sidney sporting some truly ridiculous prices. Household debt stands at 150% of disposable income and most of it is mortgage debt, which the fractionally-reserved banks have very generously offered to the usual muppets who could ill-afford it. No problem though: skies are clear and prices keep on rising like there’s no tomorrow! Actually, they don’t: prices have stalled and have now begun to decline, although at a moderate pace. Their decrease is accompanied by a sharp decline in the number of sales and a marked slowdown in construction activity: it seems to us that the unwinding has begun, particularly given that China is now beginning to crumble as well (more on the topic below). Plenty of links for the passionate investigators: here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here (where the author shares his delusion that prices cannot possibly collapse since, among other things, they may have “plateaued”: 1929 anybody?!).

Prices in Australia have now begun their long trip down, via Global Property Guide.

Debt to disposable income ratio for Australian households: pretty high and most of it is mortgage debt. Chart from one of the articles linked above.

New Zealand

Apparently, the Aussie’s neighbours aren’t doing much better. In fact, it seems they’re currently experiencing the final stage of the bubble, with relatively brisk price increases across the board and some signs of a looming slowdown. Of course, the debt to income ratio stands at a quite buoyant 150% and prices are at least 25% overvalued, but may be as much as 65% more expensive that their long term average. Our guess is that when the Australian housing market finally sneezes the NZ is going to catch a cold. More information can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here (again, delusional – or maybe self-serving - comments about the non-existence of the bubble).

NZ house prices, via Global Property Guide. And they have the audacity to claim that there’s no bubble?!

Here we have the usual wee bit of debt. Via one of the previously-linked articles.

South Africa

We have decided to include South Africa simply because we had the chance to visit it right at the height of its massive RE bubble and we enjoyed looking at then-current listings (referring to them as totally ridiculous is a huge understatement) and chat with a few chaps there about the market and we returned home deeply satisfied, with the persuasion that the market was headed for a decade or more of Buddhist-like nothingness. And in fact it seems like we were spot on, as prices have gone pretty much nowhere during the last few years, notwithstanding a relatively significant depreciation of the currency. But now it seems like the globalized inflationary race has begun to work its wonder on SA as well, with prices again starting to increase at a quite rapid pace. Whether this is just a temporary phenomenon or the beginning of a new bubble still remains to be seen. In any case, as much as SA is a lovely country, we wouldn’t buy a home there. Debt to disposable income stands at 76%, but remember that a large part of the population cannot possibly think about borrowing as they’re too busy surviving. Further info can be accessed here, here, here, here and here.

House prices in SA and YoY % change in nominal and real terms, via Global Property Guide.

North America

We’ll now quickly review the state of the housing market in the U.S. and Canada. It’s worth mentioning that Bernanke is “successfully” (depending on how you define success) re-inflating the once-burst U.S. housing bubble. Of course this is bound to generate even deeper distortions and dislocations in the economy’s structure of production. It won’t end merrily.

U.S.

The witch doctor, alternatively known as Fed Chairman, Ben S. has managed to re-start many bubble activities that were justly interrupted in the wake of the 2008 collapse. Of course this has happened at a grave cost, as unsustainable and ultimately unprofitable capital-consuming activities continue to be allowed to take place, at the expense of everyone in the economy. Housing is of course chief amongst these bubble activities and the market has experienced a strong rebound. Whether it’s going to survive the coming crisis is of course highly questionable. In the meantime, ever more people are getting sucked in, ready to be spit out in pieces once the downturn arrives (and it always arrives, although it often takes longer than anticipated). It should be clear that this whole process does nothing but inherently weaken an economy. Anyway, let’s review some data: debt to disposable income stands at 115% (whereas household debt to GDP currently is close to 90%), home prices are increasing at the fastest pace since 2006 (which was pure bubble territory) and median nominal prices for new homes are again at levels close to those registered at the last bubble’s peak. You draw your own conclusions! Here, here, here, here, here, here and here readers can find more information. Moreover we recommend this blog and all the articles published at Acting Man by guest author Ramsey Su.

U.S. home prices have begun to creep up again: a new bubble is forming? Via Global Property Guide.

Median U.S. new home prices: back in bubble territory. Chart taken from this article.

Canada

Here we have another contestant for the top prize in the category “Most overvalued RE market in the world”! Again, the culprit is the reckless monetary policy of the central bank, which has allowed bank credit (i.e. credit that is not backed by real resources) to boom. The global commodities boom has also helped in fuelling the bubble. The result is that now Canadian households have a debt to income ratio above 160% and home prices are at least 35% overvalued (but the figure may very well be significantly higher, maybe even in the vicinity of 80%). Warnings signs have begun to appear as of late, with construction activity slowing down, sales number continuing to significantly deteriorate and a series of six uninterrupted monthly price declines. More information can be found here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and finally here (look at his bright face and then ponder whether his “well-reasoned” arguments hold any value).

Canadian home prices via Global Property Guide: up, up and away!

Rest of the World

Let’s now quickly review the state of the housing market in a few more countries, before drawing our conclusions. We wan to to briefly mention that both Dubai and Hong Kong, by keeping their currencies pegged to the U.S. dollar, basically adopt the Fed’s monetary policy. As a result, their RE bubbles are sort of echo bubble, magnified by the relatively small size of their economies and by the huge foreign capital influxes. On the other hand, both Singapore and Hong Kong sport very low taxes and a remarkable level of economic freedom and are thus engaged in true wealth generating activities, which to a marginal extent mitigate the impact of the bubble.

Dubai

We couldn’t avoid mentioning Dubai, as it’s arguably the most absurd place on the earth, a big playground for His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, a child at heart with gobs of money at his disposal. "The word 'impossible' is not in leaders' dictionaries. No matter how big the challenges, strong faith, determination and resolve will overcome them.". Sure, we mere mortals can’t argue with such words of wisdom, but in the meantime we humbly suggest to include the world “bubble” in the aforementioned dictionary (“debt restructuring” is already in it). Oh, and we happen to have a nice bridge to sell, should His Highness be interested!

We were in the city of dreams (which may become nightmares) recently and we were delighted to see cranes all over the place: 2008 hasn’t taught the morons a thing! In fact evidence seems to suggest that there currently is a new speculative mania underway in Dubai’s property market. Proof of the foolishness of such RE frenzy lies in the sheer number of empty units. Again, we seriously doubt it could survive a resurgence of the 2008 financial crisis. The only mitigating circumstances are the absence of taxes and the relative degree of economic freedom, which, in an increasingly more totalitarian world, appear as ever more valuable features. More info here, here, here, here, here and here for a bit of colour!

Singapore

Singapore is another very overvalued RE market (with the only caveat mentioned above), with prices roughly 50% above their long-term average according to The Economist. Signs of a slowdown are present, although we haven’t still heard a clear popping sound. Interested readers can have a look here, here, here, here and here.

House prices in Singapore and their YoY % change, via Global Property Guide.

Hong Kong and China

Hong Kong is probably the single most overvalued RE market in the world, with Canada the only true contestant for the top spot. Prices there have tripled in less than a decade and are now roughly 70% overvalued. We explained the dynamics of the bubble above. We just want to add that the market is now in a manic blow-off stage, with prices increasing more than 20% in the last year. If we had a house there we would be rushing to sell it, not now but yesterday! Further information can be found here, here, here and here.

Hong Kong RE prices and their YoY % change: a sheer bubble is glaringly obvious. Charts from Global Property Guide.

China is a bit of a different story, quite complex and murky. We won’t analyze the market in detail here (although we do not rule out doing it in a future post): we’ll just provide some basic info and a quick overview. Real estate speculation is the national sport there and it’s also the main tool the all-knowing wild bunch of bureaucrats ruling the country uses to achieve the desired level of “growth” (i.e. an orgy of malinvestments mistaken for a mirage of prosperity). Leverage is also present in spades, notwithstanding the usually benign official statistics, thanks mainly to the so-called “shadow banking system” (i.e. a colourful potpourri of moneylenders, pawnbrokers and loan sharks). The picture is completed by the by-now famous “ghost cities”, imposing monuments to the utter madness of which humans are capable. Signs of a slowdown are present, but not yet unequivocal. It is however important to note that our Mandarin friends do not stand out for their transparency. Interested readers are welcomed to learn more here, here, here, here, here and here.

Property prices in China have experienced a “healty” increase in the last decade, via Global Property Guide.

An interesting documentary on China’s ghost cities.

Conclusion

It should be clear by now that the world at large is in the midst of an egregious real estate bubble (actually bubbles are pretty much everywhere and not only in RE, hence Jesse Colombo’s apt definition of this epoch as The Bubble Bubble, a bubble of bubbles). We have of course not covered all the countries in the world, but readers should have developed a taste for what it’s like. Those who are willing to spend some time doing further investigations can take a look at India or other emerging markets and see whether they can see any differences with the countries presented above. The takeaway is clear in our opinion: wherever you are, think twice before buying a house! Interesting speculative opportunities also abound, as shorting the stocks of banks that are heavily exposed to bubbly RE markets is likely to prove profitable, provided it’s done in an intelligent way. Exercising patience is always necessary though, as many of these bubbles could keep on going for quite some time, especially given the reckless policies currently implemented by global central banks (and we have them and their fractionally-reserved cronies to thank for this mess). Warning signs abound in many cases, but timing is always the tricky part. And of course there’s no substitute for doing your homework.

As a final note, we’re generally not prone to self-praise, but assembling this post has really been yeoman’s work and we hope that our readers will appreciate it and if so help spread it to a wider audience.